In late summer, when the heat hums on the horizon and evenings come with a lazy dusk glow, most people associate mosquitoes with a seasonal nuisance—a minor irritation at cookouts or camping trips. But in parts of the country, especially the Midwest, they are more than an itchy annoyance. They’re potential carriers of West Nile virus (WNV), a mosquito-borne disease that has long had a seasonal rhythm tied directly to weather patterns.

As someone who’s seen the rhythms of nature on the land—where soil health, water retention, and ecological balance all intertwine—it’s no surprise that the dynamics of rainfall have a big impact on more than just crop yield. They’re also a key indicator of mosquito pressure and disease prevalence.

This year, with higher-than-average rainfall, the prevalence of West Nile virus has dropped—and it’s not just coincidence. There’s solid science behind why dry conditions favor West Nile outbreaks, and why wet years, like this one, offer a subtle layer of natural protection.

Let’s dig in.

West Nile Virus: A Quick Primer (And Why It Still Matters)

West Nile virus (WNV) is part of the flavivirus family, which includes other mosquito-borne diseases like Zika and dengue. It was first detected in the U.S. in 1999 and has since become the most common mosquito-transmitted disease in North America. It circulates primarily between birds and mosquitoes, with humans and horses occasionally becoming infected when bitten by an infected mosquito—typically the Culex species.

Symptoms and Statistics

Here’s what makes West Nile tricky:

- About 80% of infected people never show symptoms. They’ll never know they had it and will recover without issue.

- Roughly 20% experience flu-like symptoms—headache, fever, body aches, joint pain, vomiting, diarrhea, or rash.

- But for about 1 in 150 people, the virus turns severe, leading to neuroinvasive disease like encephalitis (brain swelling) or meningitis (inflammation of membranes around the brain and spinal cord).

This is where concern kicks in. That tiny percentage—the 1 in 150 who get very sick—are often older adults, immunocompromised individuals, or those with underlying health conditions. They may experience permanent neurological damage, long-term memory issues, balance and coordination problems, and in rare cases, fatal outcomes.

Even if most people recover quietly, local health departments track West Nile closely—like at quarterly vector-borne disease review meetings held by the Vigo County Health Department, where public health staff examine regional mosquito and infection data. Larry, my nesting partner, works there and says West Nile always comes up. Despite its mild reputation, they’re digging into case stats because that 1 in 150 severe case rate can have serious consequences—and it’s often invisible until it’s too late.

Why It’s Still a Big Deal

- No vaccine for humans. We can’t prevent it with a shot—just avoidance and landscape management.

- Silent spread. Asymptomatic cases make it hard to track or predict outbreaks.

- It’s cyclical. Some years it’s minimal, others it spikes—especially during hot, dry summers.

- It indicates ecological imbalance. High WNV rates often reflect unnatural clustering of birds, mosquitoes, and degraded landscapes.

That’s why even in years when cases are low, it’s still brought up in public health discussions—it’s a canary in the coal mine for mosquito ecology, water quality, and land health.

Why Less Rain Means More West Nile

At first glance, you might expect more rain to produce more mosquitoes. After all, standing water is their breeding ground, right? That’s true—but only to a point. The relationship between rainfall and West Nile virus is nuanced.

1. Drought Creates Ideal Mosquito Habitats

During extended dry spells, many natural bodies of water shrink, exposing edges and puddles that become stagnant. These shallow, nutrient-rich pools, often rich in organic debris, are ideal nurseries for Culex mosquitoes—the primary carriers of West Nile virus.

On the flip side, heavier rains flush out these small breeding zones or keep water bodies moving, which disrupts egg-laying and larval development. It’s not just about having water—it’s about having the right kind of water.

2. Birds Cluster Around Shrinking Water Sources

Dry conditions force birds to gather around limited water sources—ponds, creeks, puddles—which also attract mosquitoes. This increased concentration of both birds and mosquitoes facilitates amplified transmission cycles. More mosquito bites, more viral exchange, more risk.

In wet years, birds are spread out across the landscape. Mosquitoes still bite them, but the odds of transmission drop when fewer interactions occur in condensed spaces.

3. Dry Heat Boosts Mosquito Metabolism

Mosquitoes are cold-blooded. Their activity and metabolism spike during hot, dry weather, enabling them to digest blood meals faster and lay eggs more frequently. This shorter reproductive cycle means their populations grow faster—and more generations mean more chances for virus transmission.

In contrast, frequent rainfall and cooler cloud cover can slow mosquito development, essentially throttling the whole ecological process that fuels West Nile outbreaks.

How This Year’s Rain Changed the Equation

Across regions like Illinois and Indiana, 2025 has brought exceptional rainfall. Flash flooding, saturated fields, and persistently damp conditions have dampened West Nile transmission in several key ways.

1. Mosquito Habitat Disruption

While mosquitoes do need water to reproduce, too much of it can destroy their nurseries. Frequent storms and heavy rainstorms flush larvae out of ditches, storm drains, and catch basins. This constant disruption prevents populations from stabilizing long enough to become dangerous.

2. Cooler, Cloudier Days Slow Reproduction

Consistent cloud cover and damp conditions moderate soil and air temperatures. Mosquitoes don’t thrive in cooler, unstable weather. Their feeding slows, their reproduction drops, and their life cycles stall—especially in species like Culex pipiens, which require warmth for optimal reproduction.

3. Expanded Bird Habitat Means Less Viral Clustering

Thanks to plentiful water, birds are more evenly distributed across the landscape, foraging in woodland edges, wetlands, and hedgerows. This spatial separation reduces bird-mosquito interactions, which in turn limits viral amplification and lowers transmission rates.

A Regenerative Lens: Landscape Health and Disease Resistance

For stewards of the land—people who care not just about crop yield but about ecological resilience—the connection between water, land cover, and mosquito-borne illness offers a practical lesson:

Healthy, water-balanced ecosystems create natural disease buffers.

It’s not just about killing mosquitoes. It’s about building landscapes that don’t give them an advantage. That includes:

- Shade trees and canopy cover, which cool the land and disrupt mosquito feeding cycles

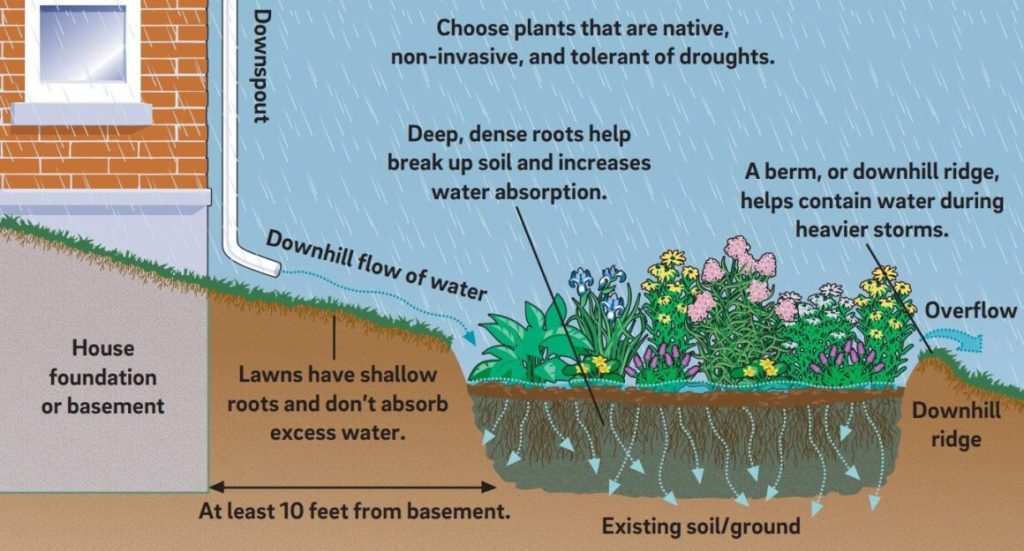

- Rain gardens and bioswales, which manage water flow without stagnation

- Ground cover and mulch, which protect soil from becoming compacted puddles

- Biodiversity, which regulates predator-prey relationships (hello, dragonflies!)

When land is hydrated, vegetated, and biologically rich, pathogens like West Nile have less room to run.

Not All Rain Years Are Equal

It’s worth noting that not every wet year brings safety. If water collects in urban containers—buckets, tires, clogged gutters—the potential for mosquito outbreaks actually increases. That’s why landscape design and management matter so much.

In rural and regenerative settings, rainfall is more likely to:

- Soak into well-structured soils

- Evaporate through plant transpiration

- Filter through cover-cropped fields and compost-rich gardens

That’s exactly the kind of land that manages water without creating mosquito nurseries.

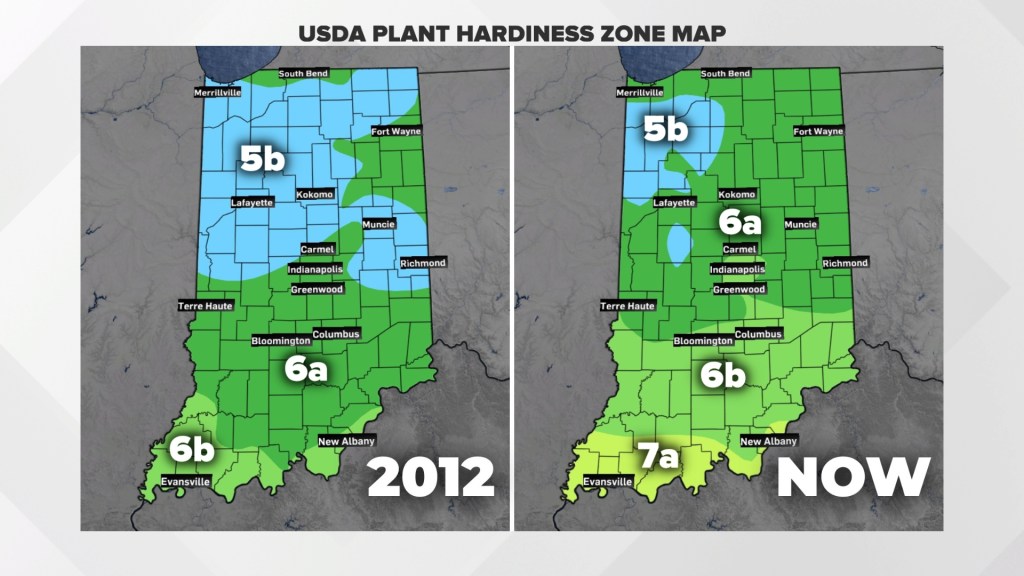

Adapting to Shifting Climate Conditions

Climate variability—more erratic rain cycles, prolonged droughts, and unexpected downpours—makes mosquito-borne illness harder to predict. Communities must develop flexible responses, including:

- Monitoring mosquito populations and bird reservoirs

- Investing in regenerative land care and water management

- Educating the public about container control and local vector ecology

- Building natural buffers like tree lines and wetlands

Rain may slow transmission, but preparedness still matters—especially with diseases that fluctuate year to year.

What You Can Do to Reduce Risk

Even if this year has brought relief from West Nile spikes, individual choices still matter. Here’s how to stay proactive:

In Your Garden or Homestead:

- Remove standing water from containers, wheelbarrows, and livestock trough rims

- Use mulch to protect soil from puddling and compacting

- Keep compost piles covered and turned to prevent soggy microhabitats

- Plant native vegetation that invites predators like frogs, birds, and dragonflies

- Build shade through trees and hedges to lower surface temperatures

In Your Community:

- Support green infrastructure like rain gardens and vegetated swales

- Report areas with consistent mosquito outbreaks

- Encourage sustainable land care and soil regeneration policies

Closing Thoughts: Rain, Resilience, and Ecological Balance

It’s tempting to frame West Nile virus as an issue of pest control alone. But the deeper truth is this: land care decisions shape disease outcomes. The rise and fall of mosquito populations aren’t just about weather—they’re about how landscapes respond to water, heat, and disturbance.

This year’s rain offered a gift of disruption—it broke the mosquito cycle, cooled the land, and spread wildlife into more balanced patterns. But the lesson endures even beyond wet seasons:

Regenerative land practices build disease resilience.

Healthy landscapes manage water wisely.

And the soil beneath our feet quietly holds the power to protect us.